Intuition in the Woods

Lessons from Twin Peaks on living with ambiguity

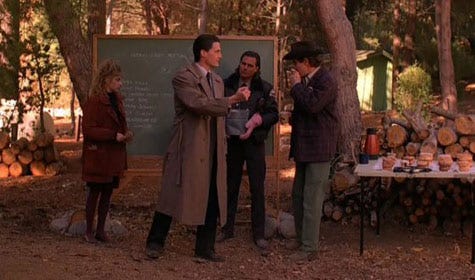

FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper is standing in the woods outside Twin Peaks, giving the local sheriff’s department a lecture on Tibet. He’s set up a chalkboard among the Douglas firs. He writes a suspect’s name on the board, “Jacques Renault”, then picks up a rock and throws it at a glass bottle positioned several yards away. Whatever rock hits the bottle - that’s the suspect he would follow up on. Whatever standard procedure the police had in Twin Peaks, or whatever rational approach the FBI would take - was thrown out of the window here.

Twin Peaks embodies a philosophy of abiding: trusting intuition, accepting mystery, finding meaning in presence rather than resolution. This connects to David Lynch’s Buddhist practice and echoes The Big Lebowski’s “Abide Guide”. The show suggests that some mysteries are meant to stay mysterious, that working through ambiguity rather than eliminating it is how we move forward. The proof came when the show itself violated this principle: when ABC head Bob Iger forced Lynch to reveal who killed Laura Palmer, Twin Peaks immediately declined. Solving the central mystery destroyed what made the show work.

In the show, Agent Cooper and the Log Lady navigate Twin Peaks through non-rational means, but in different ways. Cooper actively trusts his intuition: he receives clues about Laura Palmer’s killer through dreams and treats them as legitimate investigative leads. He reads people instinctively, immediately trusting Sheriff Truman based on gut feeling. He stays grounded through sensory presence: good coffee, cherry pie, the feeling of a place. Cooper uses intuition as a tool alongside reason. The Log Lady works differently. She’s a passive conduit. Her log, somehow connected to her deceased husband, delivers messages she doesn’t understand herself. She accepts and transmits information from a reality others can’t perceive. Where Cooper chooses to trust his instincts, the Log Lady simply receives what comes through.

This year I discovered Mark Frost’s two Twin Peaks companion books: ‘The Secret History of Twin Peaks’ and ‘The Final Dossier.’ Frost co-created the show with David Lynch in the early 1990s, and these books frame Season 3 (which aired in 2017, 25 years after the original). Frost weaves the fictional town into real American history. The narrative reaches back to the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1805, incorporates Native American mythology from the Pacific Northwest, and threads through UFO incidents, the JFK assassination, and the Nixon presidency. It’s a mystery that expands rather than resolves: each answer raises new questions. The books filled in backstories for characters I thought I knew, revealing how little I’d understood them. I’m keeping this vague because the books reward discovery. This approach, deepening mystery rather than solving it, is what Twin Peaks was always meant to do. It’s also what the original show abandoned when it revealed its central secret too early.

The third season of Twin Peaks vindicated David Lynch’s approach. With full creative control this time, he made the most uncompromising season of the series. The show revealed what happened to characters over the past 25 years while preserving what made the original work: it deepened mysteries rather than resolving them. Even after weaving in new complexities and storylines, key questions remained unanswered. Lynch proved that creative control and commercial pressure pull in opposite directions, and that the former produces better work.

We learn more from living with uncertainty than from forcing premature answers. Twin Peaks demonstrates this: meaning exists in the questions themselves, not just their resolution. In a culture that demands closure and optimizes for answers, the show offers a different approach: find presence in ambiguity, trust your intuition through the unknown, and accept that some things resist full understanding.

P.S. If you’re new to the show, consume it in this order: Season 1, Season 2, the movie “Fire Walk with Me”, then read Mark Frost’s “The Secret History of Twin Peaks”, then watch Season 3, and finally read Frost’s “The Final Dossier”.